WHAT YOU’LL LEARN:

- Why Peter threw out the old trial transcript and started fresh

- How to reframe juror bias about intoxicated plaintiffs

- The data-driven strategy behind challenging subway speed policies

- How to cross-examine for maximum outrage (and impact)

- The difference between a real study and a “rail sim”

- How demonstrative evidence and real-time vulnerability drive damage awards

Jury conditioning techniques that make asking for 9-figure verdicts possible

📍 KEY MOMENTS:

- 2:12 – Trial setup: Two cases, one station, two amputations

- 8:40 – Why Peter ignored the prior transcript entirely

- 11:24 – Jury selection: owning the facts about alcohol

- 17:15 – “You’ve all broken the law”: Crosswalk analogy + relatability

- 24:45 – The “struck list” and statistical smoking gun

- 31:12 – The aha cross: “Would you slow down 3, 2, or 1 MPH to save a life?”

- 37:08 – Transit’s refusal to change policy, even for 12 dangerous stations

- 44:30 – Qualified immunity dismantled: no real study, no defense

- 50:20 – Defense toxicologist admits: alcohol ≠ fault

- 59:45 – Live prosthetic reveal + emotional damage testimony

- 1:08:00 – How to condition a jury for a 9-figure number

- 1:14:18 – The final verdict: $103.6 million

- 1:17:02 – Trial self-care: Peter’s unexpected secret weapon

- 1:20:00 – The ripple effect: gates begin appearing in subway stations

🧰 PJI HIGHLIGHTS FOR YOUR REFERENCE:

- Duty to a Passenger – PJI 2:161

- Comparative Negligence – Intoxicated Person – PJI 2:45

- Qualified Immunity – PJI 2:225b

- Damages: Past Pain & Suffering – PJI 2:280

- Damages: Future Pain & Suffering – PJI 2:281

EPISODE 2 TRANSCRIPT

Gennady Voldz (00:04.245)

Welcome back to the Trial Bible podcast. We’re closing arguments echo louder than gavels. I’m your host Gennady Volz and today, boy, we’ve got a first class guest who just handed the New York City Transit Authority a multimillion dollar reality check. That’s right folks, joining us is the one, the only Peter S. Thomas, the Trial Titan who’s taken on

The train tightens and walked away with a verdict so big, even the MTA had to stop and check their Metro card balance. Peter, welcome to the show. How are you?

Peter S. Thomas (00:42.904)

Thank you, Gennady. ...

EPISODE 2 TRANSCRIPT

Gennady Voldz (00:04.245)

Welcome back to the Trial Bible podcast. We’re closing arguments echo louder than gavels. I’m your host Gennady Volz and today, boy, we’ve got a first class guest who just handed the New York City Transit Authority a multimillion dollar reality check. That’s right folks, joining us is the one, the only Peter S. Thomas, the Trial Titan who’s taken on

The train tightens and walked away with a verdict so big, even the MTA had to stop and check their Metro card balance. Peter, welcome to the show. How are you?

Peter S. Thomas (00:42.904)

Thank you, Gennady. Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Gennady Voldz (00:46.043)

It’s a pleasure to have you. We’ve heard the last name before Thomas. Our first guest was Dan Thomas. Any relation?

Peter S. Thomas (00:53.452)

My baby brother by 10 minutes, yeah, absolutely.

Gennady Voldz (00:56.535)

Dan Thomas was absolutely an excellent guest. Both of you come from a line of legal titans in the field. Your father was the great judge, Charles Thomas. And Judge, if you’re listening, you did good with these two boys. And we’re happy that you did everything that you could do to make them turn out the way they did.

How was it growing up in a family where your father is a judge, your brother is also in the business? Tell me a little bit about that.

Peter S. Thomas (01:33.28)

It was great. mean, it was every night at dinner, we would have conversations that were not just stimulating and exciting, but really helped to train us to think like lawyers and to problem solve and to think logically and approach situations a little differently than we were being taught, obviously, between our friends and school. So it was great. It was fantastic. I feel very fortunate.

Gennady Voldz (01:57.621)

You know, a lot of people think, do I go to law school? It’s a big ticket. It’s a big step financially to go through the process. And I’ve been telling everyone the beauty of law school is maybe not so much what you learn, but how they teach you to think and approach problems. I thought that was the biggest takeaway for me. It really made me think differently when I was talking to my friends and going about problems at work.

It completely changed the theory.

Peter S. Thomas (02:31.328)

Absolutely analytical thinking logical reasoning Taking I think it was Iraq our IR AC issue rule Analysis and conclusion and and that sort of and that’s how they taught us for legal writing But it’s also legal thinking you know if you can break down any issues into those four categories You pretty much can figure out where you’re going and how you want to proceed so

Yeah, my brother and I had been exposed to that at an early age without even knowing that we being exposed to it. Because my father would do more than just tell us about his cases. He’d ask us questions and how we thought and what we think he should say and what he should do and never really realizing that it was all just practice for our future.

Gennady Voldz (03:21.234)

Invaluable, those conversations are invaluable. Clearly they worked, both you and your brother, extremely successful trial attorneys. So I wanna set the stage here for this particular trial against New York City Transit. This wasn’t just any injury on the tracks. You have a train, you have two separate plaintiffs here and the Transit Authority trying to derail responsibility.

Tell us a little bit about the beginning details of what you got when you started this case as trial counsel.

Peter S. Thomas (03:54.83)

Well, first of all, there were two plaintiffs in this trial, Mr. Pedraza and Mr. Martinez. Mr. Pedraza’s case had already been tried once before by the attorney of record, and his name is Alan. And Alan had tried the case once before and got a verdict of $5 million from the jury, but

the jury found 60 % negligence against Mr. Pedraza for being on the subway tracks, more specifically at the Spring Street station, the number six downtown train. He was struck by a train at that station and sustained an amputation of his arm. And so being that the Transit Authority was denied an opportunity to claim qualified immunity as a defense,

and Alan thinking that a $5 million award was too little, they both appealed. And when they appealed, the court granted a new trial on all issues. But Alan had another case at the same station where we were alleging the same liability issues. And the court consolidated both actions, even though the second case, Martinez, his accident was three years later, three years after Pedraza.

They consolidated the cases for joint trial and based on the common issues on liability. So now I’m trying two cases with one jury, both sustained amputation injuries at the Spring Street station being hit by a number six downtown train. Mr. Martinez sustained a leg amputation, Mr. Martinez an arm amputation. So I’m given this case and I did something that I don’t usually do.

I didn’t even read the trial on the first case, Mr. no, sorry, Mr. Pedraza. I didn’t even read that trial transcript. I knew that they were expecting me to read the trial transcript and prepare for this case based on what has already been testified. I thought since I’m…

Gennady Voldz (06:02.1)

All right, go ahead.

Peter S. Thomas (06:05.27)

I thought since I’m coming in new, I want to take a new approach and I don’t want to repeat what was already said. Not only that, I was looking for a better verdict than had already been achieved in the first trial. So I figured if I start from scratch, I won’t be distracted, if you will, or I won’t be married in any way to any of the testimony in the prior case.

Gennady Voldz (06:26.132)

Let me see if I get this straight. You have two separate plaintiffs, Pedrazo and Martinez, both get hit, I’m sorry.

Peter S. Thomas (06:32.631)

draws up.

Pedraza with an A, not with an O.

Gennady Voldz (06:37.482)

So Rita, delete that, let’s start over. Let me see if I get this straight. We have two separate plaintiffs, Mr. Pedrazo and Mr. Martinez.

Peter S. Thomas (06:48.832)

Okay, if you’re gonna get it right, Pedraza. P-E-D-R-A-Z-A.

Gennady Voldz (06:51.68)

Pedraza, all right, had it spelled wrong. Rita deleted part two. All right, so let me see if I get this straight. You have two separate plaintiffs, Mr. Pedraza and Mr. Martinez. They’re both getting hit by the six train downtown at the Spring Street station. They both end up on the tracks of that station. Is there any other similarities between those two cases?

Peter S. Thomas (07:16.75)

Well, they both have elevated blood alcohol level in the hospital. So another way of saying is they were highly intoxicated.

Gennady Voldz (07:25.226)

Both highly intoxicated. What levels are we talking about here?

Peter S. Thomas (07:30.446)

Well, one had a 0.19 blood alcohol level, the other had a 0.21 blood alcohol level. And this was an hour or more after the accident.

Gennady Voldz (07:42.066)

And do these two guys know each other? All right, so just by… Go ahead.

Peter S. Thomas (07:44.45)

Not at all. only thing they have in common is they’re both Mexican and work in restaurants, and both working late nights and live in Brooklyn. So they were taking the six train back from their jobs in the city, back to their homes in Brooklyn, and somehow each of them ends up getting off at the Spring Street station, which is neither one of their stops, neither one of them.

had to or needed to get off at the Spring Street station but somehow found themselves getting off at the Spring Street station.

Gennady Voldz (08:20.618)

When you said that on appeal the transit authority wanted an immunity defense, what is that position that they wanted to take and thought that they would win on?

Peter S. Thomas (08:32.824)

but qualified immunity very much like when the police officers have protection from being sued if they’re doing their job if they they can’t be sued for manhandling somebody during the course of the rest this transit authorities claiming that they were entitled to the benefits of a qualified immunity you only get a qualified immunity as a municipality or quasi municipal agency like transit authority if you’ve done a study

And if you’ve done a study on the issue that is the issue before the jury, and if your study reveals that your, the basis for your decision and how you either in this case operate the trains, the speed at which the trains come into the station, if you’ve done a study and you can show a rational basis for the decisions you’ve made in light of that study,

then you could benefit from a qualified immunity and avoid responsibility because you’ve done this study. It’s very common in roadway design cases or when you have a situation where there’s an accident at an intersection, is there a need for traffic light? Is there a need for stop sign? If there are studies done that show that the rational basis for the decision was properly evaluated and analyzed and they continue to track it,

They can avoid responsibility even if it turns out it wasn’t the best decision.

Gennady Voldz (09:53.975)

All right, so let’s talk about strategy a little bit. You know going into this that we’re dealing with two drunk Mexicans after work on a track. Let’s just keep it very truthful with each other. That’s a tough fact to deal with in front of a jury. You know it, I know it, every trial lawyer knows it, every lawyer knows it when they’re picking up the case.

What do you do, whether it’s in jury selection, in opening, on direct with your client, what do you do to soften that up?

Peter S. Thomas (10:34.542)

There’s no way to soften it. You can only own it. And you can make sure that you don’t try and hide it and don’t try and run away from it. But the interesting issue in this case was that the New York City subway system is an open track system, which means there are no barriers. There are no doors. There are no separations between the platform and the tracks. Anybody can access the tracks.

And the Transit Authority knows that people who are incapacitated, people who are drunk, stoned, or stupid, I don’t know how else to describe it, use their system. Use the transit system. And their line of defense is to put a yellow line on the edge of the platform saying stand behind the yellow line and to make some announcements here and there. But nothing stops anybody from accessing the tracks. And people end up on the tracks for multiple reasons. People can be pushed.

People can jump down intentionally to get something that they’ve dropped. They could be trying to cross over to the other side. They could have a medical condition which caused them to lose their balance. They could be victims of crime and thrown on the tracks. There’s all kinds of reasons why people end up on the tracks. And the key here was that the Transit Authority knows it. And they’ve kept track of how many people actually end up on the tracks and are involved in what we call, what they call a 12-9.

That’s the code 12-9. That’s the code for somebody being struck by a train.

Gennady Voldz (12:03.56)

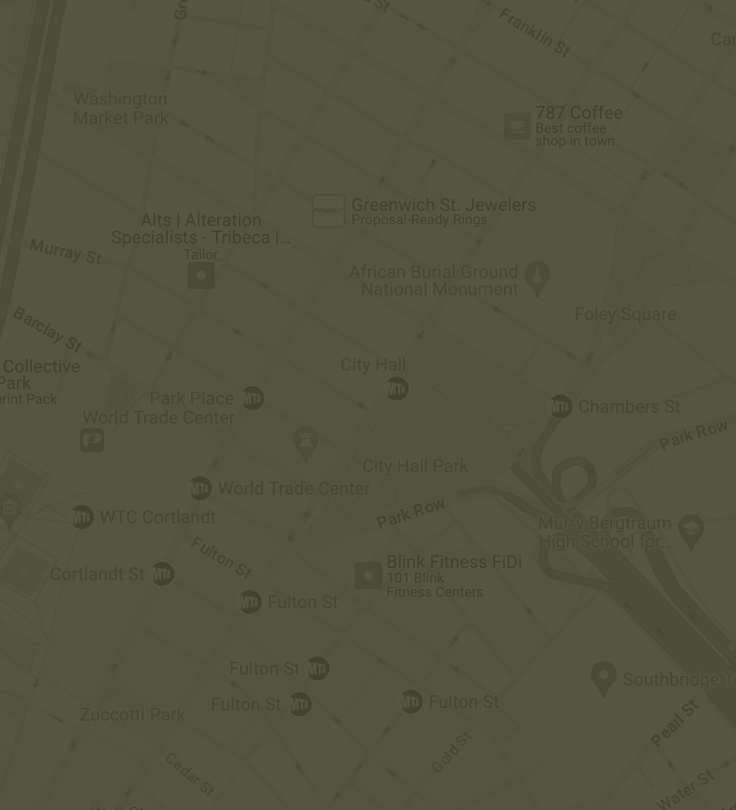

All right. Let me stop you Pete. I want to go back to, I pulled up the photo. This was one of the exhibits during your trial, right? And this is the Spring Street station. Is this showing where they were struck?

Peter S. Thomas (12:13.4)

correct.

Peter S. Thomas (12:21.976)

This is showing where Mr. Martinez was struck. Mr. Pedraza was struck closer to where that garbage can is in the photograph. So just about 30 feet away, 30 feet closer to the north end of the station where the train comes into the station was Mr. Pedraza. Mr. Martinez was about 30 feet down the track.

Gennady Voldz (12:29.654)

Yep.

Gennady Voldz (12:42.806)

So I wanna go back to my original question. How do you start to present to your jury pool or your jury that these two men were highly intoxicated and despite their intoxication levels, they were not at fault for this accident? What do you specifically do in this case?

Peter S. Thomas (13:03.916)

It starts in jury selection. And part of getting a jury that is going to be open to considering these claims is to bring that fact out, to tell the jury that my clients, both of them, on two separate occasions, they don’t know each other, were both struck by trains at the same station, and that when they arrived at the hospital, they both had elevated alcohol level.

and blood alcohol level, and then neither one of them is going to be able to tell you how they got there. If any of you feel that those facts alone are enough to cause you to render a decision before hearing the evidence, please let me know. And you, as you might believe, the majority of the room put their hands up and said, your client was on the track, shouldn’t be there.

Your client was intoxicated, what was he doing intoxicated on the tracks? The client got hit by a train and doesn’t know how he got hit? Yeah, no, I’ve already made up my mind. So by being as open and upfront with these facts in the very beginning, before I got even into the details as to how long the case was going to take, because a lot of times when you tell a jury pool this is going to be a five week trial, half the people say I don’t have five weeks to devote to this. So even before I got into the fact that it was going to be a five week trial,

I said I want to tell you some facts here which we’re not disputing and see if that affects any of your feelings or opinions about being a juror in the case.

Gennady Voldz (14:28.36)

Other than them being intoxicated, did you have any other particularly bad facts on this one that you wanted to put out there?

Peter S. Thomas (14:36.184)

Well, the fact that neither one of them knew how they got there. The testimony at the trial that was elicited was all the, both of them, they remember leaving work. And next thing you know, when they woke up, they were in the hospital with one less limb.

Gennady Voldz (14:51.008)

So there’s no dispute that the train hit these two individuals, right? What is the transit’s position with respect to defending liability?

Peter S. Thomas (14:55.822)

true. Correct.

Peter S. Thomas (15:04.737)

The Transit Authority took the position that they have an exclusive right of way on the tracks, that no one is allowed on the tracks. The only people on the tracks should be safety workers or contractors of the Transit Authority, and all that is planned in advance. Nobody belongs on the tracks. Nobody’s supposed to access the tracks. And if you’re on the tracks, you’re in violation of the rules.

Gennady Voldz (15:32.214)

You’re a trespasser.

Peter S. Thomas (15:34.252)

Your trespasser, exactly. That’s what they call it. They call them trespassers. So one of the things I did to try and also, I guess, soften that issue was the first thing I did when I walked in there, actually the very first thing I did when I walked into the jury room was I said to all the jurors, raise your hand. Everybody put your hand up. Everybody. And I looked at the defense attorneys. You too, put your hands up. Everybody puts their hands up.

And I said, leave your hand up only if you have never crossed the street against a red light. Leave your hand up only if you always wait for the traffic light to turn green before you cross the street. And I looked around the room and all the hands went down. Even the defense attorney’s hands went down. And I said, okay, now I know I’m talking to a room full of New Yorkers.

Gennady Voldz (16:03.702)

Okay.

Peter S. Thomas (16:33.644)

And I said to them, you have all broken the law. You all violated vehicle and traffic law by crossing the street against the red pedestrian signal. But what you’ve also did was you assessed your own risk. You knew that even though the light was red for you, you could cross without issue because there were no cars coming or whatever it is. Then I said to them, would you do the same thing if you were pushing a wheelchair?

or if you were holding the hand of your four-year-old nephew. Of course not, because now your assessment of risk is different. You’re now responsible for somebody else. So you’re not going to take those chances. Well, the New York City Transit Authority is responsible for everybody in their system. And this is a case about speed. And I said to them, and as we all learned probably in grade school, speed kills. Speed maims.

Speed can change people’s lives in an instant. And I made this case about speed. The speed of the train coming into the Spring Street station.

the downtown number six train in particular, because of the speed of that train, the configuration of this station, and the likelihood of somebody being on the tracks in that station, and the inability of a train operator to see if there’s anybody or anything on the tracks coming into that station became the theme of my case.

Gennady Voldz (18:00.055)

So really you brought up a pretty new theory of liability against the New York City Transit Authority that I don’t know if anyone has brought up this particular, this specific type of case saying you guys are pulling into the station too quickly, specifically the Spring Street station.

Peter S. Thomas (18:22.754)

That’s right. And we were able to take this information that we got from the Transit Authority, specifically a document called a struck list. And a struck list is kept because every time somebody pulls the emergency brake or the emergency brake is engaged, the central command has to be notified. And when there are situations where the train operator is the one who hits the emergency brake because there’s someone on the tracks or something on the tracks,

And if there is a person on the track and the train hits the person, it’s called a 12-9, 12-9, that’s the code. And they keep track of all these 12-9s. And we were able to get this struck list from 1987 through 2006. And actually, sorry, I’m sorry, yeah, we were able to get this struck list from 1987 through 2016. And when we looked at the struck list, we found statistically,

Gennady Voldz (19:04.054)

2016, I believe, right?

Peter S. Thomas (19:16.482)

that the Spring Street station, specifically the number six train at Spring Street, had a five to nine time higher rate of incidents of people being struck by trains, depending on which 10 year period you’re looking at. But still, an elevated percentage of people struck by trains at this station. And one of the things we came up with was that as the southbound or downtown number six train pulls into that station,

It’s a big deep curve that the train operator is blind, has a very, very limited sight into the station until he gets into the station. So at a speed of 27 to 30 miles an hour, if there’s somebody on the tracks, there’s no way that train is gonna be able to stop. Most other stations in the system are straight tracks. So you can see down the track into the station even before the train gets into the station, not at this station.

Gennady Voldz (20:12.352)

Did you have any kind of exhibit showing the jury what the station looked like?

Peter S. Thomas (20:18.604)

Yes, in the course of discovery, we were able to get lots of documents, including architectural drawings. And one thing we got was the Spring Street Station site plan, or the platform station plan. And that was drafted, I believe, in 1987. And we took that document and we blew it up. We blew it up very large. We needed multiple easels to keep, yeah, there it is. We needed multiple easels to keep it level so the jury could see it.

And this is the Spring Street station plan that shows the southbound number six train coming into the station. And the thing that we argued was if you see the entrance to the platform is at the northern portion of the station. So when people come into the station, that’s the north end, that arrow that says north end of station, that’s the very start of where

the train comes into the station. But if you look a little to the left, you see the platform entrance. Yeah, right there. That platform entrance. There’s only one entrance to this platform. And it’s at the northernmost part of the station. So when you have somebody who’s impaired by drugs or alcohol or maybe prescription medications, whatever it may be, they’re asked to come into that station and stand in an area where the train comes in the fastest.

Gennady Voldz (21:22.996)

Right.

Peter S. Thomas (21:46.348)

The safest part of that station would be the further end, the other end of the station, the south end of the station, where the train would be coming in at its slowest rate of speed. So the other thing is, if you get off at that station, you have to go out and pay again to get back in. There’s no way to get to the other side without having to pay the fare again. So what we found was that at this particular station, people would cross the tracks to get to the other side.

So they didn’t have to pay to get back into the train system.

Gennady Voldz (22:19.072)

So to get back to your theory of liability challenging their speed, their speed policy, what kind of defense did they put on? What kind of witnesses did they put on to try and defend that this was a perfectly normal speed for the train to go and this is just how things are done?

Peter S. Thomas (22:26.126)

speed policy. Correct.

Peter S. Thomas (22:43.116)

They put on train operators. They put on rail safety people. They put on the chief of planning and operations. They put on expert witnesses. And the theme of all these witnesses that were testifying for the defendants were, we are a rapid transit system. We have to find ways to make the trains run faster while still being safe. We cannot slow the trains down.

Gennady Voldz (23:10.982)

anything pop out, anything happen during your cross, I’ve seen you in action. I know that cross examination is a lot of fun for us trial guys. It’s where a lot of the fireworks start to happen. And, you know, I even tell the jury sometimes in jury selection, you okay with me ruffling a few feathers if it means getting down to the truth? Are you okay with that? No one’s going to hold that against me.

I know you do that as well. I know you like to have a lot of fun in your cross. So did anything happen during cross examination of their witnesses that kind of tilted the tide?

Peter S. Thomas (23:52.918)

Yes, well there were two witnesses in particular who I think really not only were being honest but couldn’t defend with the type of questions that I was asking and the information they revealed turned out to be shocking. The jury was shocked. The jury was in fact mad. There’s no other way to describe it. They were angry when they heard the testimony of these two witnesses on these two issues.

First I’ll tell you there was the train operator. And the train operator was testifying about how many different stations there are in the transit system that have curved stations, the tracks curve when they come into the station, and that there’s no issues and things like that. And I said to him, the recommendation by the plaintiff’s expert was that the train be slowed down to 15 miles an hour before it enters the station.

so that in the event somebody is on the tracks, the train can stop in time to avoid hitting them. And I said to him, is there a speed limit sign in the tunnel that would restrict the train coming into that station to reduce speed? He said, no, there is not. I said, would you agree that there should be one? And he did not want to answer that question.

He said, it’s above my pay grade that no one’s ever asked me. It’s not my job. And then I asked him sort of a hypothetical. Let’s say that somebody in upper management said to you, Mr. Train Operator, yes or no? Should we put a speed limit sign reducing the speed of the train coming into the station to 15 miles an hour instead of the 30 miles an hour that the train comes into right now? What would you say? And he said,

I would probably say yes, we should put a speed limit sign there. So that was an aha moment, but there was another aha moment that I think was even bigger than that.

Gennady Voldz (25:57.121)

Hold on, I just wanna highlight the art of the question, the art of the answer that you’re gonna get. You’re setting up a question where either he’s gonna agree with you or what’s the alternative? He’s gonna look like an asshole and say, absolutely not, I don’t think so, I don’t care about the safety of what happens on my tracks. You’re setting him up with an impossible question.

Peter S. Thomas (26:25.282)

Well, we know what the proper answer should be from a safety point of view. But when you are less concerned about safety and more concerned about meeting your time schedule, then you’re going to give the answer that he gave. I knew that no matter how he answered the question, I would be able to come back with the facts of this case and ask him how he reconciles his response in light of these facts.

Gennady Voldz (26:38.409)

I love it.

Gennady Voldz (26:51.946)

That’s called trial art, folks. If you can come up with questions on Cross where you cannot lose, you’re off to a great verdict. All right, so what was the second one?

Peter S. Thomas (27:05.71)

Okay, so the second one was their chief of planning and operations. This was a guy who was actually involved in making policy for the Transit Authority in terms of regulating speed or not regulating speed of the trains coming into stations. And I do want to tell you that there are certain stations that the trains are regulated in terms of speed. For example, the 42nd Street station has a speed limit. There are other trains, other, uh, uh,

stations throughout the system that have regulated speeds for multiple reasons. But this question that I asked of their chief of planning and operations.

I said, sir, would you agree to slow the train down by three miles an hour coming into the Spring Street station if it would save a life or a limb? And he said, no. I said, sir, would you slow the train down by two miles an hour? The number six train downtown coming into Spring Street station.

by two miles an hour if it would save a life or a limb. He said no. And of course, when I said, sir, would you slow the number six train down by one mile an hour coming into the Spring Street station if it would save a life or a limb? And he said, no, we are a rapid transit system. We don’t slow the trains down.

Based on that answer, the jury was visibly moving around in their chairs. The jury was folding their arms, shaking their heads. I even heard one or two jurors sucking their teeth. Like, couldn’t believe what he just said. So the way the question was asked was really important. And the fact that it was asked the rule of threes. I could have just said,

Peter S. Thomas (29:09.646)

You know, would you slow the train down by one, two, three miles an hour if it would save a life or a limb? I don’t think it would have had the same effect. But by breaking down that question into three parts, with three miles, two miles, one mile, really brought the point home. And the jury was visibly upset.

Gennady Voldz (29:29.152)

So he really put, they really put all their eggs in one speed basket and they said, we won’t slow down the train. We have passengers to deliver from point A to point B and our priority is moving those passengers first and then safety second.

Peter S. Thomas (29:49.038)

And I went one step further and I said, well, if you slow the train down, that might mean less revenue for you. And he tried to sort of shake that off and say, it’s not about revenue. We have to be reliable system that moves people safely. I said, but isn’t it about money? Aren’t you still a business? Aren’t you trying to make money? And of course he said, it’s not about the money. Now what they did was we asked.

Gennady Voldz (30:15.73)

It’s always about the money. It’s always about the money. All these cases that we talk about, it’s someone focusing more on money than on the public’s safety. it’s just set. Go ahead.

Peter S. Thomas (30:19.298)

That’s right.

Peter S. Thomas (30:31.17)

But let me tell you what they did that really, I think, was not very smart on that part. We asked that they slow the train down at one station, the Spring Street station.

They took that request and they went and said, well, if we slow the train down at Spring Street, we have to slow it down at every station. And then they did an analysis for how much of a delay it would cause in the course of a day by slowing down each train coming into every station. And they said, because we can’t do that, we’re not going to slow the train down at any station. So again, it’s their own, I’ll call it stupidity. I’ll call it nonsense.

We asked that you focus on one station and they heard that and said, we have to do it at every station or we don’t do it at any stations. Nobody asked you to slow the trains down at every single station. There are plenty of stations in the system that have a long straightaway that the train operator can see into the station and be able to engage the brake long enough to be able to stop before entering the station, let alone hitting somebody that’s on the tracks. But there’s only 12 stations in the entire system.

that are seriously restricted because of the curvature of the station and the curvature of the tracks coming into the station. 12 out of 492 stations, only 12. Would it have been so difficult for them to focus on those 12? That’s not what they did.

Gennady Voldz (31:56.161)

So relating it back to the PJI charges that were applicable on this case, which is two colon 161, common carrier duty to a passenger and two colon 176, duty to the public persons on or near tracks. Both of those PJI charges have a reasonably foreseen language in there. Other than the struck list,

Was there anything else that gave notice to the New York City Transit system that this was happening and that they should have made change a long time ago?

Peter S. Thomas (32:36.418)

Well, we called a statistician. We had a statistics expert come in and analyze the information. And he was able to tell the jury that on average, two to three people a week are struck by trains within the system. And if that’s not notice, then I don’t know what is. Their own struck list was the notice that we used to show that they were very well aware for all kinds of reasons that people end up on the tracks.

and we excluded, we intentionally excluded suicides. Now not every single train strike can be determined as a suicide, but those that clearly were because they either told somebody they were gonna do it or left a note or something like that, we excluded those numbers from our statistics.

Gennady Voldz (33:23.318)

Tell our listeners a little bit about the New York City bill and assembly that was tried to be passed in February of 2011.

Peter S. Thomas (33:33.772)

right, the Crespo bill. There was a bill that was introduced that required, that would have required the trains to stop before entering the station, to not just protect people on the tracks, but also to protect the workers, the transit workers. Remember, both train operators in this case were out of work for one for a year and one for many months seeking psychological and emotional counseling.

for their experience involved in these accidents. And it also slows down the train by hours. We were asking that they slow the train down to 15 miles an hour, which would have been 9.8 seconds longer than the train would have taken to come into that station if it didn’t slow down. When you hit someone, train is out of service for an hour or two or more.

So realistically, when you think about it, asking them to slow the train down to add 9.8 seconds to that stop is not really unreasonable. But when you hit somebody and the train is out for two or three hours, that’s going to cause definitely a backlog in ability to get people where they’re going.

Gennady Voldz (34:49.664)

Talk to me about your strategy when it came to the qualified immunity defense. How did you start to prepare the jury for that and how did you work it throughout the trial?

Peter S. Thomas (35:03.202)

Well, since I knew they did not do a formal study of this issue, the only study they did was how fast can they operate the trains and how fast can they operate the trains without derailing the train and how fast can they operate the train without throwing people out of their seats. And they labeled it two different things. They said there’s the comfort speed and there’s a safety speed. The comfort speed, the speed the trains can go where people could still be comfortable.

The safety speed was the speed that you can operate the train without affecting the equipment. know, derailing the train or having the train hit the platform edge as it comes in. So those are the two speeds that they considered. They never considered slowing down the train at certain stations because of limited sight line of the train operator. So since I knew they never did that study, I pointed out to their experts and their witnesses, where is the study that you did?

that considered this issue. And they said, well, we did a train simulation. I said, what do you mean? They said, we used a computer program called RailSim, R-A-I-L-Sim. RailSim, and we put information in there and the RailSim program told us that we could continue to operate the trains at maximum attainable speeds. So they didn’t do a study, they did a computer.

program analysis and that was it. And I made a big deal about a study means you start with a hypothesis, you do research, you do testing, and you either prove or disprove your hypothesis. That’s a study. Did you do that? And they said, no. We did a rail simulation. They never used actual trains. They never did it during the, at night or even off site.

where they have testing in Connecticut. They have a simulated train car that’s about a mile and a half long. They never did any reconstruction or any attempt to use real trains and real stations to do their analysis. They just use a computer program, and that simply is not enough.

Gennady Voldz (37:20.631)

So you made a big distinction between what it is that they claim to their study was, in fact, was not specific enough to be deemed a real study when it came to the Spring Street station and the speed of this six train coming in on the northbound side.

Peter S. Thomas (37:29.816)

Mm-mm.

Peter S. Thomas (37:41.176)

Correct. had to prove that they one, did a study. Two, they did a study of the issue that’s before the jury. Three, that the decisions they made based on that study were rational. And four, that they continued to monitor it to see if there were any changes that needed to be made.

Since they never did a bona fide study, it didn’t matter how many computer simulations they did, how much analysis they did, how much number crunching they did, they never did a study. And since they never did a study, they were never going to be entitled to qualified immunity.

Gennady Voldz (38:13.313)

Did the trial judge allow the qualified immunity defense on the verdict sheet for them?

Peter S. Thomas (38:20.206)

Yes, he did. He gave questions on the verdict sheet to the jury to ask the jury whether in fact they did a study, whether that study was there was a rational basis for the decisions they made. He asked all those relevant questions on the verdict sheet. The verdict sheet was I think 25 pages.

Gennady Voldz (38:37.079)

So when it came to, this is New York County, New York County is bifurcated, the jury’s hearing both liability and damages at the same time. When it came to the liability verdict, you had mentioned in the beginning of this show that Mr. Pedraza’s case previously had a 40 % liability verdict against Mr. Pedraza, 60 % against the.

Peter S. Thomas (39:00.878)

No, 60 % against Mr. Pedrazo.

Gennady Voldz (39:04.747)

Let me redo that, Reeder, let me redo it. Let’s talk about the liability portion here. You had mentioned earlier in the show that the original trial that happened about five years prior to this, that the jury found Mr. Pedraza 60 % at fault for his own accident, correct? After Mr. Thomas steps into the courtroom and does his razzle dazzle and tells these jurors,

Peter S. Thomas (39:24.76)

That’s correct.

Gennady Voldz (39:34.613)

what they need to hear, what was the liability against the New York City transit system.

Peter S. Thomas (39:42.19)

Well, in this case, there were three entities on the verdict sheet. It was the Transit Authority, it was the train operator, and then each plaintiff. The jury found no negligence, no responsibility against either of the train operators, no negligence, no responsibility against either of the plaintiffs, and found the Transit Authority 100 % responsible in both cases based on their failing to appreciate that speed at which the train comes into the station

is just too great for a train operator to be able to stop before hitting somebody who’s on the tracks.

Gennady Voldz (40:17.899)

Give us a little bit of the closing arguments on liability. Why being intoxicated, having no idea how this happened, where they were at the time, why it’s not their fault.

Peter S. Thomas (40:34.52)

You know, I was expecting and anticipating an argument from the defense that would have connected the alcohol consumption to their being on the tracks. And they called a medical toxicologist to testify. And their medical toxicologist took the alcohol levels at the hospital, extrapolated back to the time of the accident to testify and render an opinion that at the time of the accident, both of them had

I think one I think had a must have had nine drinks and the other had seven drinks to have a blood alcohol content of what was listed in the hospital report. And on cross examination, I said to that expert, okay, we can see they both had elevated blood alcohol levels in the hospital. How does that put them on the tracks? She goes, I don’t know. I said, how does the elevated blood alcohol level support the position

that they’re responsible for being on the tracks themselves. She goes, it doesn’t. So their own expert was not able to connect the alcohol use and their being on the track, especially when I said to her, are you aware that either one of them may have been victim of a crime and pushed on the tracks? May have misstepped that had nothing to do with alcohol? May have just fallen asleep and rolled onto the track? I mean, there’s all different types of reasons. And their expert said, yes, any of those things is possible. That’s not my job here is to make that determination.

So the one witness that they were relying on to try and causally connect the alcohol consumption to their position on the tracks was not able to do that based on the limited information that she was given. So I argued to the jury, the defendants have not met their burden of proving that the plaintiffs were negligent. We don’t deny they increased levels of alcohol. But are you supposed to take the train if you’re intoxicated? Better than getting behind the wheel of a car and driving.

And how often does the New York City subway system know that people who take the trains are impaired, either by drugs, alcohol, prescription medications, failing to take their prescription medications? And then I mentioned, what happens on New Year’s Eve? Aren’t the subways packed with people going in and out of the city to celebrate? And how many of them do you think are intoxicated, above the legal limit to be able to drive? And she said, I’m sure many, many of them.

Peter S. Thomas (43:01.656)

So the Transit Authority knows that people who use their subway could be intoxicated, have elevated blood alcohol levels? yes, absolutely. So it was two parts. There were two parts of that testimony. One, she couldn’t causally relate. And two, the Transit Authority very well knows that the people that use their system are intoxicated. She then said, you’re not allowed to drink in the subway. Okay, what if you drank before you got into the subway? She says, yeah, you can’t stop that.

They know about it. So once again, those facts were not properly addressed by the defense to show to the jury that either one of these plaintiffs was responsible themselves for ending up on the tracks. They didn’t know how they got there. So I argued in my summation, the defense has failed to meet their burden of showing you facts in this case that the plaintiffs themselves were responsible. And the jury agreed.

Gennady Voldz (44:00.903)

I had the pleasure of sitting in on the closings for both you and the New York City Transit System and

You know, I’m always surprised that defendants who dig their heels in to a position that sounds ludicrous to me. The fact that they continue to emphasize that our ethos in this case is to move as quickly, move passengers as quickly and safely as possible. He kept saying it in that order, quickly and safely. And you know, just the position of those words.

is so powerful rather than saying safely and quickly when you’re defending a case. Some of the parts that you started saying were just so powerful. I’m just going to mention a few because I took notes as you were giving your closing statement. You said,

Well, I love it when you refer back to some of the some of the stuff that the defense counsel does when when they were giving their closing, they had this PowerPoint and he was trying to be all fancy with technology. You got up there and said, I don’t have a PowerPoint, but I have the facts and the law. And the truth is here, the New York City Transit Authority has zero value for human life. So powerful.

for a jury to hear that. You said they’re not giving you reasons, they’re giving excuses. And when it comes down to it, I’m gonna quote you here, if you’re on the track, there’s a chance you won’t make it.

Peter S. Thomas (45:46.062)

That’s right.

Gennady Voldz (45:47.617)

hearing that as a New Yorker who’s taken the subway system, let alone the disaster that the subway system has become post COVID, knowing how dangerous of a place this subway system is, and knowing that people fall in, people get pushed in, people drop their belongings on these tracks, to say it in those words, if you’re on the track, there’s a chance you won’t make it, was the crux of this case.

And it was really the transit authority standing there and saying, yeah, we know that. And our job is to move people quickly. too bad. Congratulations on the liability verdict. I want to get to damages. You knew before you went into this that you were going to be asking for a large number because of the injury itself. Tell us again, what were the injuries to Mr. Pedraza and Mr. Martinez?

Peter S. Thomas (46:46.69)

Mr. Bedraza was a 46 year old restaurant worker and he lost his left arm. And Mr. Martinez was a 23 year old restaurant worker and he lost his leg. Below the knee.

Gennady Voldz (46:58.775)

So hold on, both of them lost the limb. Sounds tragic, sounds significant, but again, I’m sitting in this courtroom and I’m looking at these two guys. They looked good, to be honest with you. They were cleaned up, they were wearing suits. They didn’t look like they were hobbling around or anything like that. They looked like two normal guys walking around New York City.

Peter S. Thomas (47:03.182)

Correct.

Gennady Voldz (47:26.859)

How did you get the jury to?

empathize with their pain and suffering that they’ve been through as a result of this.

Peter S. Thomas (47:38.626)

Well, first I showed the jury photographs of both Mr. Bedraza and Mr. Martinez as to what they look like with their missing limbs. And then while they were on the witness stand, I asked Mr. Bedraza, can we see your shoulder, where your arm used to be? And we watched him disrobe, unbutton his shirt, pull his shirt to the side, and he showed the the site where his arm was amputated at the shoulder.

for Mr. Martinez, he took his pants down and of course I prepared him in advance so he wasn’t, you know, gonna embarrass himself but he was wearing shorts under his pants and he took his pants down and he took off his prosthetic leg and he showed the jury his prosthesis that was wrapped in black electrical tape and gray duct tape. I said, why do you have the tape there? He says, because it’s eight years old and it’s cracked.

and it doesn’t fit right and I don’t have the money to buy a new one. So here this eight-year-old prosthetic limb is being held together with electrical tape and duct tape and the jury’s impression was how can this be? How can this guy even, you know, live a normal life when he doesn’t can’t even afford a new prosthesis, a well-fitting prosthesis? And the testimony from our experts was that he’s going to need a new prosthesis every three to four years.

That’s how much wear and tear it gets. And here it is now eight years post-accident and he’s still with the same prosthesis. It was very powerful. The jury watching them navigate, just even getting dressed and getting undressed was very, very powerful from the witness stand.

better than any day in the life video, better than any blow up photographs that I can show them. They were watching them in real time, how they operate and how they get along.

Gennady Voldz (49:37.141)

You’re no rookie to asking for a lot of money. And I know you make it a point to tell the jury as quickly as you can. I’m going to be asking for a lot of money. Give us a little bit of the gems, if you will, on how you go about doing that, conditioning this jury to understand that the only right verdict here is a large one. How do you do that?

Peter S. Thomas (50:06.744)

Well, in this case, because the Transit Authority really didn’t have much of a defense, I was able to use the fact that you have two plaintiffs with missing limbs. This isn’t just a sprained ankle case. They’re going to have lifelong disabilities. They have limitations and restrictions in everyday activities for the rest of their lives.

but it was also about letting the Transit Authority know that you don’t appreciate the strategy that they’ve employed. And this stick your head in the sand type approach of, you shouldn’t have been there and you wouldn’t have gotten a hit. It was a way of getting the jury not just to consider what fair and adequate compensation would be for the injuries proven and for the damages proven, but also to let the Transit Authority know this has to change. Something has to be done.

and I tried to balance both of those issues but primarily you have Mr. Pedraza 13 years since the accident without his arm and another 22.2 years on his life expectancy.

Mr. Martinez nine years without his leg since the accident and another 46.7 years on his life expectancy. So I was able to use the future life expectancy as a way of letting the jury know that’s where the big money is, is in their futures.

Gennady Voldz (51:30.219)

When do you start talking about money to the jury?

Peter S. Thomas (51:33.966)

jury selection right away. tell them the only thing the court allows in terms of compensation is money. I’m not apologizing for it. I’m letting you know right now that at the end of this case, all you can do is award a sum of money that will fairly and adequately compensate the plaintiffs for all damages. And our job here, my job here is to make sure that my clients do not get shortchanged. No discounts.

pain and suffering is not on sale. So even if you do find split liability, meaning the plaintiffs are partially responsible and the defendants are partially responsible, we are still entitled to know what 100 % compensation would be for the damages proven. Don’t do the math yourself.

Gennady Voldz (52:19.445)

What was the pretrial offer on this case?

Peter S. Thomas (52:24.354)

zero.

Gennady Voldz (52:28.011)

The verdict, how much was it?

Peter S. Thomas (52:33.39)

The total verdict for both plaintiffs came out to $103.6 million. The jury awarded 20, as I told them in my summation, Mr. Pedraza has been 13 years since the accident. They awarded $20 million for past pain and suffering.

and they gave him $25 million for future pain and suffering. So Mr. Pedraza, who only had a pain and suffering claim, got $45 million. Mr. Martinez, they gave him $10 million for past pain and suffering, and they gave him $47 million for future pain and suffering. And then they gave him another $3.5 million for…

future medicals, including new prosthesis and diagnostic testing and follow-up visits for therapy. So the total came out to $103.6 million between the both of them.

Gennady Voldz (53:33.459)

If we took $103.6 million in singles, how many train cars do you think we’d have to fill up? That’s not a verdict. That’s a train load of justice. Talk to me about the experts for damages. What kind of experts did you use to bolster your damages claim?

Peter S. Thomas (53:47.522)

Yes.

Peter S. Thomas (53:55.778)

Well, we had a prostitutes, somebody who understands the value and the need for prosthetic devices. We had a life care planner who was a medical doctor. We had a economist who was able to take the life care planners projected figures and put a chart together for the jury as to what with inflation, what it would be over time. We had a orthopedic surgeon who talked about the surgical procedures.

And what was very interesting about this case is, again, one guy lost his arm at the shoulder, one guy lost his leg just below the knee, but there was not a lot of blood. And there was not a lot of, you know, you would think there’d be carnage on the tracks. The hot train wheel against the hot rail.

helps to cauterize the wound, even though the train ran over their limbs and cut off their limbs. Because it’s so hot, it actually helped to cauterize the wound and prevented a loss of blood. Mr. Martinez was under the train for about 40 minutes before they were able to extract him. In the usual situation, you lose your leg, you could bleed out and not make it. But by virtue of the heat from the rails that they were on, helped to cauterize the wound and limit the loss of blood.

Gennady Voldz (55:15.735)

How long was this trial?

Peter S. Thomas (55:18.136)

The trial was five weeks.

Gennady Voldz (55:20.513)

How do you stay sane? How do you stay with it? How do you stay on top of the next day when you’re going five weeks? What do you do?

Peter S. Thomas (55:29.28)

It’s just one witness at a time, really. I don’t prepare for the last witness first. I try and anticipate, you know, I know who my witnesses are going to be and I ask defense counsel who you’re to call tomorrow, who you’re to call the next day to try and get an idea as to who’s going to be called. So, for example, on their last witness, I didn’t even start to prepare for that last witness until I was about three and half weeks into the trial.

Gennady Voldz (55:54.101)

Is there something that you do, walk us into your personal life a little bit if I may. Is there something that you do either just before trial or even during the trial to kind of recenter yourself, to find that peace within the storm that helps you realign of how you’re gonna present this case?

Peter S. Thomas (56:17.602)

Well, what I can tell you is most trial lawyers are just frustrated actors or musicians or entertainers. And I guess I fall into that category as well. I play guitar.

And when I come home after a stressful day or when I’m done getting ready, I’ll pick up my guitar and just play a few songs just to decompress, just to get back to sort of center. And it works very well for me. I don’t have any quirky sort of yoga tips or meditations that I do. I just like to play a little guitar and that helps me to reboot and you know.

Go to the next thing. Listen, I make more money as a lawyer than I do as a singer, so.

Gennady Voldz (56:59.863)

You brought up music, so I’m gonna ask you this one. You’re up at bat, you’re coming into the courtroom hot, what’s your walkout song?

Peter S. Thomas (57:10.542)

You know the song that keeps playing in my head is Eye of the Tiger. know, Rocky’s Eye of the Tiger. Maybe I’m a victim of my own upbringing, but that to me was like the triumph song. That was the song. That’s like the underdog. That’s like the when you hear that you know that somebody just beat the odds. So Eye of the Tiger.

Gennady Voldz (57:30.487)

You’re playing that after the verdict or as you’re walking in on day one.

Peter S. Thomas (57:35.522)

day one in the middle of the trial and of course at the end of the case. Yeah, that’s the recurring song playing in my head.

Gennady Voldz (57:43.123)

I love that. All right. This wasn’t just a verdict. This sent a message to our transit system and it did so in a big, big, big way. You did something I believe here that will not go unnoticed and

You’ve already established change within the transit systems culture. You started to get a few pictures after the verdict. Tell us what those pictures were of.

Peter S. Thomas (58:23.242)

Actually, one of them was from a juror on the case who said, guess we’re starting to make a difference. And it’s a picture, it wasn’t at the Spring Street station, it was another station, I believe it was the Fulton Street station. And they put up these gates. They’re small little sort of waist high type gates that are on the platform.

that are meant to prevent somebody from accessing the platform. When the train pulls into the station, there are no doors at that location. That’s right, you have it up right now. And these gates may help to deflect somebody from falling onto the tracks or prevent somebody from being pushed onto the tracks. It doesn’t take a lot. And had this been in place at the time of both Mr. Martinez and Mr. Pedraza’s accident, there’s a very good chance that neither one of them would have ended up on the tracks.

Gennady Voldz (59:16.705)

So you see them here folks, I’m putting up a photo of it. I think this is the photo that came from the jurors, is that right Pete? If you live in New York and you take the subway system and you start to see these gates, I want you to thank Peter Thomas because he’s the guy that was the courtroom conductor, the justice engineer.

Peter S. Thomas (59:23.266)

I believe so, yes.

Gennady Voldz (59:44.353)

Today’s featured verdict slayer that really made a difference for New Yorkers with this verdict, not just for Mr. Pedraza, Mr. Martinez, but everyone that rides the New York City transit system. Peter, I wanna thank you personally for coming onto the show. Thank you for the trial justice that you continue to deliver case after case.

It’s a pleasure having you as a friend, as a mentor. Always a pleasure speaking with you.

Peter S. Thomas (01:00:18.36)

Thank you very much for having me. Yeah, this is just one of the many cases that I’ve been involved in over the years. And I’m very proud of the outcome. I’m proud of the justice that we were able to get for both of the plaintiffs. And I’m glad to see that the Transit Authority is actually paying attention. I mean, does it take a hundred million dollar verdict for them to start considering safety? I guess the answer to that question is yes, because within a week of the verdict, these gates started going up. And…

I hope that this is just the beginning of more safety gates or other safety mechanisms that they can put in place to truly avoid something that they know happens on a regular basis. People access the tracks for all kinds of reasons. This may help to prevent them from actually ending up on the tracks.

Gennady Voldz (01:01:08.179)

Excellent job, Pete. Folks, thanks for riding with us on Trial Bible. Remember, when the other side brings a train, you bring the truth with torque. We’ll see you guys on the next one.